|

Reframing suffering: buddhist mindfulness techniques as tools for philosophical counselling

Reenmarcando el sufrimiento: técnicas budistas de atención plena como herramientas de asesoramiento filosófico

Richa Singh Central University of Allahabad, India https://orcid.org/0009-0003-3383-268X

|

|

|

INFORMACIÓN DEL ARTÍCULO |

ABSTRACT/RESUMEN |

|

Recibido el: 23/07/2025 Aceptado el: 29/9/2025

Keywords: Philosophical counselling, Buddhist mindfulness, value-based therapy, existential suffering, cognitive therapy

Palabras clave: Asesoramiento filosófico, atención budista, terapia basada en valor, sufrimiento existencial, terapia cognitiva |

Abstract: This study investigates the role of Buddhist mindfulness techniques as foundational values in the emerging field of philosophical counselling. Bridging Eastern contemplative traditions and Western philosophical practice, the paper argues that mindfulness understood not merely as meditation but as active, value-oriented awareness; can significantly contribute to the goals of philosophical counselling. Both traditions prioritize self-awareness, ethical reflection, and the alleviation of suffering through insight rather than clinical diagnosis. Drawing on the Buddhist concept of the “Second Arrow,” the paper illustrates how mindfulness can help individuals differentiate between inevitable pain and the optional suffering caused by reactive thought patterns. The research further explores how mindfulness, grounded in the Pali concept of sati, encompasses memory, attentiveness, and ethical clarity, making it a potent tool for value-based dialogue and emotional clarity and resilience. By situating mindfulness within the framework of non-clinical, philosophical dialogue, the study challenges conventional therapeutic models and highlights a humanistic, integrative approach to counselling. This paper proposes that the synthesis of Buddhist mindfulness and philosophical counselling not only enhances individual well-being but also contributes to a broader discourse on wisdom, agency, and ethical living in contemporary society.

Resumen: Este estudio investiga el papel de las técnicas budistas de atención plena como valores fundamentales en el campo emergente del asesoramiento filosófico. Tendiendo un puente entre las tradiciones contemplativas orientales y la práctica filosófica occidental, el artículo sostiene que la atención plena, entendida no solo como meditación sino como conciencia activa y orientada a los valores, puede contribuir significativamente a los objetivos del asesoramiento filosófico. Ambas tradiciones dan prioridad a la conciencia de uno mismo, la reflexión ética y el alivio del sufrimiento a través de la introspección, en lugar del diagnóstico clínico. Basándose en el concepto budista de la “segunda flecha”, el artículo ilustra cómo la atención plena puede ayudar a las personas a diferenciar entre el dolor inevitable y el sufrimiento opcional causado por patrones de pensamiento reactivos. La investigación explora además cómo la atención plena, basada en el concepto ‘Pali de sati’, abarca la memoria, la atención y la claridad ética, lo que la convierte en una herramienta potente para el diálogo basado en valores y la claridad emocional y la resiliencia. Al situar la atención plena en el marco del diálogo filosófico no clínico, el estudio desafía los modelos terapéuticos convencionales y destaca un enfoque humanista e integrador de la terapia. Este artículo propone que la síntesis de la atención plena budista y la terapia filosófica no solo mejora el bienestar individual, sino que también contribuye a un discurso más amplio sobre la sabiduría, la agencia y la vida ética en la sociedad contemporánea, |

Introduction

Although counselling is often saw as a modern practice, its fundamental essence; guiding individuals through challenges, has ancient roots. Religious teachers, philosophers, and sages have long addressed human suffering through dialogue and reflection. In this context, the Buddha stands out not merely as a spiritual leader but as a Bhaiṣajyaguru - a master physician, or "Medicine Buddha", whose teachings offered psychological and existential relief. The Dhamma which he taught was like a medicine which cured the problem of suffering of the people and showed them the way leading to enduring happiness. He was concerned with the moral psychological problems of the people which assumed various forms. He found out the roots of the problems which were diverse or complex in nature and he found out their solutions also in diverse ways. On the other hand, medical practitioners have been doing counselling for curing diseases, which involves advice regarding lifestyle and application of Medicine but at the end, all therapists, including Philosophical counsellor do have similar aims.

Both Buddhist mindfulness techniques and philosophical counselling seek to alleviate suffering by fostering introspection, moral clarity, and self-awareness. These traditions emphasize dialogue, critical inquiry, and the cultivation of values distinct from medicalized or pathologized treatments. This paper argues that mindfulness-based approaches rooted in Buddhist thought offer practical, value-oriented frameworks that align seamlessly with the aims of philosophical counselling.

Philosophical Counselling: Foundations and Principles

Philosophical counselling emerged in the 1980s as a non-clinical approach to addressing existential and moral problems through reasoned dialogue and reflective inquiry. Jon Kabat-Zinn gives the most popular definition of Philosophical Counseling. In his word, "Paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally" (Kabat-Zinn, 1990, p. 4). Rather than diagnosing pathology, it aims to cultivate clarity, meaning, and ethical understanding.

Schuster (2008) defines philosophical counselling as a dialogical method that uses philosophical tools to help individuals reflect on life events and choices. It empowers clients to explore dilemmas not through medication or diagnosis, but through deeper questioning of beliefs, values, and assumptions.

Three core tenets underpin philosophical counselling (Li, 2010):

1. Non-pathologizing approach: Clients are not “patients” but individuals confronting philosophical challenges.

2. Leading by values: Counselling aims to clarify and guide individuals by their value systems.

3. Dialogical method: The process is conducted through structured, thoughtful dialogue rather than prescriptive treatment.

The importance of this fundamental principle lies in the emphasis that one's sufferings or problems are caused by confusion in ideas, and the clarification of ideas could help with relieving one's sufferings and problems. One of the clearest distinctions from psychotherapy lies in this commitment to philosophical dialogue. For example, consider the case of a monk experiencing depression due to a conflict between spiritual vows and family desire. While traditional psychiatric interventions failed, philosophical counselling enabled him to make meaning of the situation and transition from confusion to clarity through existential reflection. This case demonstrates that value conflicts, often mistaken for psychiatric disorders, can be resolved through philosophical inquiry.

As Martin (2006) explains, such cases often involve moral conflict rather than medical illness. Here, tools from philosophy; like Socratic dialogue, virtue ethics, or existential thought, are better suited than clinical models.

In this context Neimeyer states:

Common sense tells us that persons suffering from symptoms of major depression- fatigue, sleeping problems, feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and suicidal ideation, with a severity that sends them to seek professional help, are not in peak mental health. This is in accord with the authors’ cognitive therapy orientation, which suggests that by changing how one thinks about or regards any event in life, we can modify the level of distress it engenders. For thanatologists, this approach also fits in well with the meaning-making or narrative approaches familiar to most practitioners in the field." (Neimeyer & Sands, 2011, pp. 9-22).

Philosopher Lou Marinoff (2001) classifies depression into four types, based on etiology: (1) genetic, (2) substance-induced, (3) trauma-based, and (4) existential, arguing that existential crises often benefit more from philosophical counselling than from medication or psychotherapy.

Philosophical counselling is particularly effective for the fourth type, when depression arises from moral or value-based dilemmas. This is especially true when the suffering stems from moral ambiguity or life transitions rather than clinical pathology. This approach overlaps significantly with mindfulness-based techniques drawn from Buddhist philosophy.

According to Marinoff, the first type of depression is a physical illness requiring the help of psychiatrists or other physicians. The second type is "a physical or psychological dependency" that also requires medical attention. The last two types of depression can benefit from "talk therapy." Specifically, the third type can benefit from psychology and sometimes from philosophical counselling. "But in the fourth scenario--by far the most common one brought to counsellors of all kinds--philosophy would be the most direct route to healing.” (Martin, 2001.) In this regard, Fromm (2002) distinguishes between two types of meditative techniques that have been used in psychotherapy: (i) auto-suggestion used to induce relaxation; and (ii) meditation "to achieve a higher degree of non-attachment, of non-greed, and of non-illusion; briefly, those that serve to reach a higher level of being" (Fromm, 2002, p. 50). Fromm attributes techniques associated with the latter to Buddhist mindfulness practices. (Fromm, 2002)

Yet what distinguishes philosophical counselling is its intentional grounding in wisdom traditions, where healing is not merely about symptom reduction but about the cultivation of ethical clarity and self-understanding. This is where philosophical counselling naturally overlaps with Buddhist mindfulness, especially as interpreted in traditions that emphasize insight (vipassanā) over merely calming the mind (samatha). Both traditions encourage a reflective stance toward suffering, values, and identity. This makes it particularly compatible with Buddhist mindfulness practices, which prioritize awareness, non-reactivity, and liberation from illusion. Buddhistic mindfulness practices have been explicitly incorporated into a variety of psychological treatments. More specifically psychotherapies dealing with cognitive restructuring share core principles with ancient Buddhistic antidotes to personal suffering.

Furthermore, this emphasis on values, dialogue, and clarity also underpins Buddhist mindfulness, particularly as reframed in cognitive and therapeutic contexts. The next section explores how these traditions intersect conceptually and methodologically.

Buddhist Mindfulness: Classical Foundations and Interpretive Debate

Mindfulness, or Sati in Pāli (Smṛti in Sanskrit), is a foundational element of Buddhist thought. Often translated as "bare attention" by Nyanaponika Thera, its deeper meaning encompasses clear comprehension (sampajañña), vigilance (apramāda), and remembrance of the Dhamma (Van Gordon et al., 2014; Sharf, 2014). All three terms are sometimes (confusingly) translated as "mindfulness", but they all have specific shades of meaning. Georges Dreyfus has also expressed unease with the definition of mindfulness as "bare attention" or "nonelaborative, nonjudgmental, present-centered awareness", stressing that mindfulness in Buddhist context means also "remembering", which indicates that the function of mindfulness also includes the retention of information.

According to Bryan Levman, "the word Sati incorporates the meaning of 'memory' and 'remembrance' in much of its usage in both the suttas and the [traditional Buddhist] commentary, and ... without the memory component, the notion of mindfulness cannot be properly understood or applied, as mindfulness requires memory for its effectiveness" (Levman, 2017, p. 21). However, what does mindfulness really mean?

Bhikkhu Bodhi (2011) clarifies that while Sati originally connoted memory, the Buddha repurposed it to signify lucid awareness. This awareness is both ethical and cognitive, enabling one to remember one's values and intentions in each moment. He stated that:

But we should not give this [meaning of memory] excessive importance. When devising a terminology that could convey the salient points and practices of his own teaching, the Buddha inevitably had to draw on the vocabulary available to him. To designate the practice that became the main pillar of his meditative system, he chose the word sati. But here sati no longer means memory. Rather, the Buddha assigned the word a new meaning consonant with his own system of psychology and meditation. Thus, it would be a fundamental mistake to insist on reading the old meaning of memory into the new context.… I believe it is this aspect of sati that provides the connection between its two primary canonical meanings: as memory and as lucid awareness of present happenings.… In the Pali suttas, sati has still other roles in relation to meditation, but these reinforce its characterization in terms of lucid awareness and vivid presentation. (Bodhi, 2011.)

In the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta the term Sati means to remember the dharmas, whereby the true nature of phenomena can be seen, which means, mindfulness is a quality that every human being already possesses, it’s not something you have to conjure up, you just have to learn how to access it. The Theravada Nikayas prescribe that one should establish mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) in one's day-to-day life, maintaining as much as possible a calm awareness of the four upassanā: one's body, feelings, mind, and dharmas, such as,

· Kāyānupassanā (the six sense-bases which one needs to be aware of)

· Vedanānupassanā (contemplation on vedanās, which arise with the contact between the senses and their objects)

· Cittānupassanā (the altered states of mind to which this practice leads)

· Dhammānupassanā (the development from the five hindrances to the seven factors of enlightenment)

The four upassanā have been misunderstood by the developing Buddhist tradition, including Theravada, to refer to four different foundations. These practices aim not only to develop concentration but also to cultivate insight into the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self-nature of experience—core principles in Buddhist soteriology (Polak, 2011).

Furthermore, here I would refer to the Milindapañha, which explained that the arising of Sati calls to mind the wholesome dhammas. (Sharf, 2014) It means "moment to moment awareness of present events", but also "remembering to be aware of something". In this context Buddhadasa said, “the aim of mindfulness is to stop the arising of disturbing thoughts and emotions, which arise from sense-contact.” (Buddhadasa, 2014, p. 115) Although, according to American Buddhist monk Bhante Vimalaramsi's (2015) , the term mindfulness is often interpreted differently than what was originally formulated by the Buddha. In the context of Buddhism, he offers the following definition:

Mindfulness means to remember to observe how mind's attention moves from one thing to another. The first part of Mindfulness is to remember to watch the mind and remember to return to your object of meditation when you have wandered off. The second part of Mindfulness is to observe how mind's attention moves from one thing to another. (Bhante Vimalaramsi, 2015, p. 4)

However, the mechanisms that make people less or more mindful have been researched less than the effects of mindfulness programs, so little is known about which components of mindfulness practice are relevant for promoting mindfulness. In order to answering these here we present the concept of philosophical counselling and the reason behind is, these both concept (counselling and Buddhists mindfulness) based on a unique subject matter and goal that aims to assist people to deal with life events in an effective manner and aimed at wisdom.

Buddhist Counselling as Value-Oriented Philosophy

Buddhism, particularly in the Mahayana tradition, introduces the Bodhisattva ideal, adding a collective, compassionate dimension to counselling. Here, personal healing is interwoven with ethical responsibility and altruism. Mindfulness, in this context, becomes a means of awakening, not just a stress-reduction tool.

Contemporary interpretations, especially in the West, have often reduced mindfulness to a stress-reduction technique or emotional regulation tool. While these applications are valuable, they risk neglecting the full ethical and philosophical dimensions of sati. Teachers like Jon Kabat-Zinn have sought to reintroduce mindfulness into secular contexts (e.g., in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction), but even Kabat-Zinn acknowledges its Buddhist roots and universal aims of reducing suffering and dispelling delusion (Kabat-Zinn, 2005).

Other scholars, such as Georges Dreyfus and Robert Sharf, have criticized the oversimplified definition of mindfulness as “non-judgmental present awareness,” arguing that such terms overlook its ethical backbone. In Buddhist practice, mindfulness is inseparable from intention, right view, and the pursuit of awakening.

The mindful pause can prevent misperceptions from arising. As Ruth King noted: "Simply stated, we perceive something through our senses. There is a sense organ, and a sense object-eyes see, ears hear, nose smells, body feels, tongue tastes, and mind thinks. Once we perceive, we habitually jump to thoughts and feelings about what is being perceived. These thoughts and feelings, rooted in past experiences and conditioning, then influence the mood of our mind. When perception, thoughts, and feelings are repeated or imprinted through experiences, they solidify into view or belief. View then reinforces perception. This cycle becomes the way we experience and respond to the world." (King, 2018)

Moreover, mindfulness is not limited to meditation. It is a life skill applicable to speech, action, and daily conduct, supporting the philosophical counselling ideal of living an examined, ethical life. Thus, philosophical counselling can benefit immensely from Buddhist insights, offering pluralistic, non-pathologizing frameworks that promote growth, clarity, and inner freedom.

Thus, any integration of mindfulness into philosophical counselling must recover these deeper dimensions. Mindfulness is not only a method for calming the mind—it is a lens through which one discerns reality, questions attachments, and makes value-aligned choices; this orientation that makes mindfulness a powerful complement to philosophical dialogue.

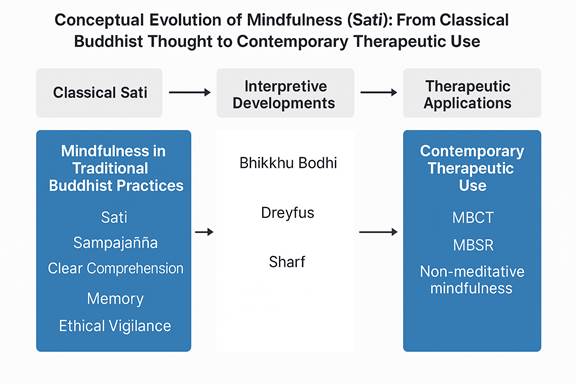

Figure: Conceptual Evolution of Mindfulness (Sati)

Mindfulness Beyond Meditation: Talk-Based

Techniques

While contemporary interpretations of mindfulness often focus on meditation, traditional Buddhist contexts also emphasize non-meditative applications. Techniques such as mindful speech, ethical behaviour, and introspective dialogue are pivotal in therapeutic and philosophical interventions.

The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā ("mental development"). Bhāvanā can involve cultivating virtues such as patience, forbearance, equanimity, wisdom, and compassion. Vipassanā and samatha are described as qualities which contribute to the development of mind (bhāvanā). Vipassanā is commonly used as one of two poles for the categorization of types of Buddhist practice, the other being samatha. Various traditions disagree which techniques belong to which pole. (Schumann, 1974.) According to the contemporary Theravada orthodoxy, samatha is used as a preparation for vipassanā, pacifying the mind and strengthening the concentration in order to allow the work of insight, which leads to liberation. Though both terms appear in the Sutta Pitaka, Gombrich argues that the distinction as two separate paths originates in the earliest interpretations of the Sutta Pitaka, not in the suttas themselves. (Gombrich, 1997)

In Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), non-meditative mindfulness exercises help clients identify and reframe their thoughts and emotions (Linehan, 1993). These approaches mirror Buddhist practices like Right Mindfulness (Sammā-Sati) and Right View (Sammā-Diṭṭhi), both crucial in navigating suffering without aversion and/or attachment.

Such methods align closely with philosophical counselling’s emphasis on value clarification, self-awareness, and narrative reconstruction—tools that enable clients to reframe distressing experiences as opportunities for growth and ethical reflection.

Furthermore, when we go from Theravāda Buddhism to Mahāyāna, a new dimension is added to the Buddhist counselling. It is that of Bodhisattva’s altruistic mission. Here I want to consider Mahayana way of counselling as a part of diversity and not a part of hierarchy. It is based on the idea that suffering is a part of life, and that problems can be worked through to achieve freedom from suffering. A Buddhist counselling approach that uses mindfulness and cognitive training to help clients understand stressful situations. Non-meditation-based mindfulness exercises are specifically used in dialectical behaviour therapy. It may also incorporate traditional talk therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). (Linehan, 1993)

The use of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction is supported by the strongest level of evidence. To show this, we can take here a Buddhist parable from Sallatha Sutta, called- 'The Second Arrow of Buddha' as an example. According to the core Buddhist psychology models of the "Two Arrows of Pain" and "Co-dependent Origination" (PRATITYASAMUTPADA), pain is the resultant of bodily and mental factors, which can be regulated by meditation states and traits. Here we investigated how pain and the related aversion and identification (self-involvement) experiences are modulated by focused attention meditation (FAM), open monitoring meditation (OMM), and loving kindness meditation (LKM), as well as by meditation expertise.

The Parable of the Second Arrow: A Philosophical Analogy

A pivotal Buddhist teaching—the Parable of the Second Arrow—illustrates the difference between pain and suffering (Sallatha Sutta, SN 36.6). The Buddha explains: In Buddhist teachings, the parable of the second arrow goes as follows:

The Buddha once asked a student, "If a person is struck by an arrow, is it painful?

The student replied, "It is" The Buddha then asked, "If the person is struck by a second arrow, is that even more painful? " The student replied again, "It is". The Buddha then explained, "In life, we cannot always control the first arrow. However, the second arrow is our reaction to the first. And with this second arrow comes the possibility of choice. The Buddhists say that any time we suffer misfortune; two arrows fly our way. Being struck by an arrow is painful. Being struck by a second arrow is even more painful.

This second arrow symbolizes the mental elaboration—self-blame, resistance, fear—that transforms inevitable pain into avoidable suffering. As Haruki writes: "Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional." (Haruki, 2009, p. 7) This pain turns into suffering in its extreme stage. We get to see a clear distinction between pain and suffering under this parable of second arrow of Buddhism. Well, it said that according to modern psychology (not to mention ancient Buddhism), therein lies the difference between pain and suffering. However, the two are not the same thing! Pain is what happens to us, suffering is what we do with that pain. While changing our perception of this concept may be difficult, it is possible. We can avoid or lessen our actual suffering based on what we choose to do with the pain we experience.

Buddhism teaches that the fundamental source of all suffering is this very attachment to or aversion to experience (Bercholz & Kohn, 1993.). For example, if we lose a loved one, we cannot get rid of that pain, but instead of asking ourselves, why did this happen to me? Could I have saved them? Instead, we can say to ourselves that I am not the only one with whom this has happened, I have done what I could, and I should try to do my best in such situation in future also.

There is a sense of resistance to it - not accepting it, not allowing it to be there, and accepting the reality of the situation. We fight with the reality of the way things are right now and so we turn the pain into suffering, or we add suffering on top. There is an equation that is often used in ACT which is:

Pain x Resistance = Suffering

The more that you resist or deny or fight or argue with the pain- which is already there, the more suffering you experience. That is a useful story to remember whenever you have any kind of demanding situation. It could be difficult internal experiences - there could be difficult emotions like sadness, anxiety, frustration, or anger, or it could be to do with difficult thoughts; it could be difficult sensations like literal physical pain or chronic pain.

Although, we are only human, and we may be overcome by feelings before we know it, even that is life. It would be abnormal not to experience feelings when major events happen. A mindfulness training will get us through the punctured tire unscathed, but major events in life like birth, death, disease, or divorce will not be always overcome with merely a meditative attitude. These kinds of arrows will also hit us, eventually. It will not always be possible to prevent the second arrow from hitting us. We will be sad, angry, afraid, even have self-pity, be depressed, etc. As Buddhist nun, Pema Chodron has suggested "Meditation practice isn’t about trying to throw ourselves away and become something better. It is about befriending who we are already. The ground of practice is you or me or whoever we are right now……that’s what we study, that’s what we come to know with tremendous curiosity and interest." (Chodron, 1993, p. 27)

Thus, mindfulness enables a pause between stimulus and reaction. Viktor Frankl (2017) articulated this gap as the essence of human freedom: "Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response."

Our power is in the space that we can create between stimulus and response. Creating that space is the key to avoiding the second arrow. Here we find another equation that is we can use as a treatment, which is:

Pain x Acceptance = Freedom

As Frankl famously said, "Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way." (Frankl, 2017, p. 55)

Let us get an example, we cannot even imagine the pain that a woman feels while giving birth to a child, but still that labour pain is not become suffering for her because her pleasant experience is associated with that pain. At that time, above any negative situation in his mind, there is a feeling of happiness that he gets from seeing his child. It never means that his pain is less in any respect, but his positive thoughts related to that pain stop that pain from turning into suffering. In other circumstances, it may not be possible that we can associate any positive thought with pain, but we can try to stop that negative thought associated with pain, so that the pain remains but does not turn into suffering. And while we cannot control our outside environment, we can, with practice, change this pattern of shooting a second arrow after the first. There are two highly effective exercises which can practice in order to circumvent this all-too-human response to life. First, noticing the pattern of the second arrow; second, practicing kindness to yourself when you see it.

Integrating Mindfulness into Philosophical Counselling

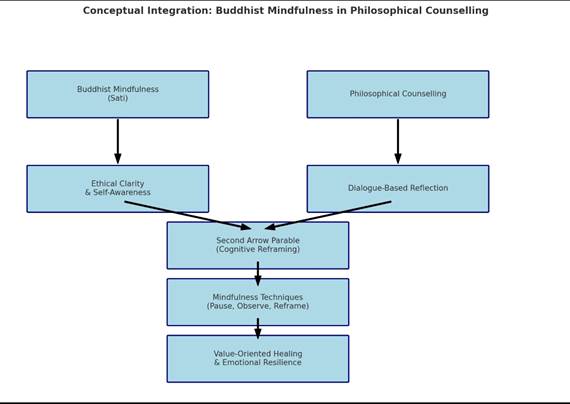

The integration of Buddhist mindfulness into philosophical counselling is not merely additive—it is synergistic. Both traditions are oriented toward self-awareness, value-based reflection, and freedom through insight, rather than symptom eradication. Key areas of alignment include:

(i) Ethical Grounding: Mindfulness in Buddhism is inseparable from ethics (sīla). Similarly, philosophical counselling helps clients examine and act in alignment with their values.

(ii) Dialogue over Diagnosis: Like Buddhist teacher-student inquiry (kathā), philosophical counselling privileges open-ended dialogue and questioning over labels.

(iii) Transforming Suffering: Both traditions view suffering not as pathology but as an opportunity for growth and wisdom.

(iv) Agency and Freedom: Mindfulness emphasizes awareness and choice; counselling emphasizes autonomy and responsibility.

Importantly, mindfulness here is not limited to formal meditation. As Buddhadasa and others suggest, it includes mindful speech, ethical action, and attentiveness in daily life. This “talk-based mindfulness” aligns well with counselling conversations and can be directly employed in sessions without requiring meditative training.

Furthermore, Mahāyāna Buddhism adds the Bodhisattva ethic, a commitment to collective well-being. This dimension expands the scope of counselling from personal relief to social compassion, aligning with humanistic and dialogical values in contemporary philosophy.

A Value-Based Therapeutic Dialogue: Practical Techniques

Mindfulness-based philosophical counselling does not require esoteric practices. It offers a grounded set of conversational tools rooted in self-reflection, presence, and ethical clarity. Instead of demanding advanced meditative training, here some simple techniques can be adapted into counselling practice:

1. Pause and observe: Encourage clients to close their eyes and tune into inner dialogue. Ask them to momentarily stop, breathe, and tune into their inner experience. Even a brief pause can interrupt reactive patterns.

2. Differentiate arrows: Help clients distinguish between identify the primary pain (fact) and secondary suffering (reaction). Primary pain: The objective fact (e.g., loss, failure). Secondary suffering: The emotional reactivity or judgment layered upon the fact. Ask: “What is the fact, and what is my story about it?”

3. Reflect and reframe: Guide clients to examine habitual thoughts, like ask; “What am I telling myself about this?” & “Is this narrative helpful or harmful?” This reflects the Buddhist principle of Yoniso Manasikāra (wise attention).

4. Cultivate acceptance: Emphasize self-compassion, non-judgment, and presence. Introduce the formula: Pain × Acceptance = Freedom Acceptance is not resignation, but an ethical stance of compassion and clarity. Clients learn to respond rather than react.

5. Respond mindfully: Shift from reactivity to purposeful, value-aligned action to create Self-Kindness as Ethical Grounding. Encourage clients to relate to themselves as they would to a friend. As Phödrön (1993) writes: “Meditation practice is not about throwing ourselves away and becoming something better. It is about befriending who we are.”

These steps offer clients tools to deconstruct habitual suffering patterns and access clarity, presence, and ethical orientation, hallmarks of both mindfulness and philosophical living. These techniques illustrate how mindfulness can be applied in counselling without formal meditation. When clients begin to observe their thoughts and emotions with non-judgmental awareness, they start to shift from identification to insight; from suffering to understanding.

Not surprisingly, in terms of clinical diagnoses, MBSR has proven beneficial for people with depression and anxiety disorders; however, the program is meant to serve anyone experiencing significant stress. (Segal et al., 2002.) Although, this is just an example. There are various of mindfulness-based teaching available in Buddhists tradition, which can truly lead the significant role in the perspective of philosophical counselling. Kabat-Zinn, a one-time Zen practitioner, goes on to write: "Although at this time, mindfulness meditation is most commonly taught and practiced within the context of Buddhism, its essence is universal. Yet it is no accident that mindfulness comes out of Buddhism, which has as its overriding concerns the relief of suffering and the dispelling of illusions". (Kabat, 2009, pp. 12-13)

Conclusion

This study has explored how Buddhist mindfulness; particularly when understood in its original context as sati, or ethical awareness, can be meaningfully integrated into the practice of philosophical counselling. The dialogue between these two traditions reveals deep conceptual harmony: both reject pathologizing models, emphasize the cultivation of self-awareness, and focus on values as a means to address suffering.

The parable of the Second Arrow provided a central framework for this dialogue. By helping individuals distinguish between unavoidable pain and avoidable suffering, it offers a cognitive and ethical tool that empowers clients to recognize and deconstruct reactive patterns. In philosophical counselling, this becomes not only a technique but a principle: to shift from habitual reaction to thoughtful reflection grounded in personal meaning.

The paper also highlighted how non-meditative mindfulness techniques, such as mindful speech, inquiry-based reflection, and value clarification, can enhance therapeutic conversations. These methods are accessible, culturally adaptive, and consistent with both Buddhist and philosophical aims: liberation from confusion, living ethically, and acting with clarity.

Moving forward, more empirical research is needed to explore how these integrated practices affect client outcomes. Comparative studies between mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-informed philosophical counselling could offer valuable insights. Additionally, developing training modules that blend these traditions may help create more inclusive and reflective counselling practices.

Ultimately, integrating Buddhist mindfulness into philosophical counselling is not just about borrowing techniques—it is about rethinking counselling itself as a wisdom-based practice, where healing emerges not through control or correction but through awareness, acceptance, and ethical dialogue.

References

Bercholz, S., & Kohn, S. C. (1993). An introduction to the Buddha and his teachings. Barnes & Noble.

Bhante Vimalaramsi. (2015). A guide to tranquil wisdom insight meditation. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. In Investigating the Dhamma.

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu. (2014). Heartwood of the Bodhi Tree. Wisdom Publications.

Chödrön, P. (1993). The wisdom of no escape and the path of loving-kindness. Shambhala.

Frankl, V. E. (2017). Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Fromm, E. (2002). The art of being. Continuum.

Gombrich, R. F. (1997). How Buddhism began: The conditioned genesis of the early teachings. Munshiram Manoharlal.

Haruki, M. (2009). What I talk about when I talk about running. Vintage Book edition.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Dell Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. (10th anniversary edition) Hatchette Books.

King, R. (2018). Mindful of race: Transforming racism from the inside out. Sounds True.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Levman, B. (2017). Putting smṛti back into sati: Putting remembrance back into mindfulness. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, 13, 121–150.

Li, B. (2010). The three fundamental principles of philosophical counseling.

Martin, M. W. (2001). Ethics as therapy: Philosophical counseling and psychological health. International Journal of Philosophical Practice, 1(1).

Martin, M. W. (2006). From morality to mental health: Virtue and vice in therapeutic culture. Oxford University Press.

Neimeyer, R. A., & Sands, D. C. (2011). Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: From principles to practice. In R. A. Neimeyer et al. (Eds.), Grief and bereavement in contemporary society (pp. 9–22). Routledge.

Polak, G. (2011). Reexamining jhana: Towards a critical reconstruction of early Buddhist soteriology. UMCS.

Schuster, S. (2008). Philosophical counselling. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 8, 219–223.

Schumann, H. W. (1974). Buddhism: An outline of its teachings and schools. Theosophical Publishing House.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford Press.

Sharf, R. (2014). Mindfulness and mindlessness in early Chan. Philosophy East and West, 64(4), 933–964.

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., Griffiths, M. D., & Singh, N. N. (2014). There is only one mindfulness: Why science and Buddhism need to work together. Mindfulness, 6, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0379-y