The mangrove ecosystem

is characterized by a complex array of tree and shrub species that have evolved

to thrive in the intertidal zones of tropical and subtropical coastlines

globally. These species have developed a tolerance to waterlogged soils and high

salinity conditions (Pomareda & Zanella, 2006). This highly productive and

intricate ecosystem contributes significant nutrients to coastal marine waters,

benefiting seagrasses and various commercially important species (Gaxiola,

2011). Mangroves are typically found along coastlines, estuaries, coastal

lagoons, wetlands, and river mouths. Their ecological significance lies in the

roles that their organisms play in maintaining coastal balance and protection,

providing spawning and feeding grounds for species ranging from fish to

crustaceans, while also offering refuge to crabs, mollusks, and nesting areas

for shorebirds. Economically, mangroves are valued for their role as habitats

for fish species, bark tannins, and wood used in various artisanal and commercial

applications (Olguín et al., 2007).

The richness of larger

mollusks (malacofauna) associated with mangrove ecosystems significantly

influences their biocenotic diversity. Abiotic factors such as salinity

(Flores, 1973), temperature, seasonality, and soil composition regulate

(Newell, 1958) patterns that determine species distribution, density, and

adaptability in varying environments. Biotic factors like predation,

competition, and food availability limit distribution (Connell et al.,

1961; Haven, 1971), in addition to interactions with other factors such as

exposure and distance from the shore (Franz, 1976). Invertebrate communities

within mangrove ecosystems display variations in species density and abundance

by zone, throughout the ecosystem, and across seasons (Jiménez, 1994), often

leading to dominance by a few species that are highly adaptable to

environmental changes. This differs from sandy beach communities where factors

such as larval recruitment (specifically for mollusks, not juvenile fish),

nutrient availability, and environmental conditions—including desiccation and

thermal variation—can have markedly different impacts (Pfaff & Nel, 2019).

However, abundance and diversity may also be influenced by habitat

fragmentation or pollution (Cárdenas-Calle & Mair, 2014).

Mollusk populations

associated with mangrove substrates generally comprise species that reside in

the sediment as ectofauna and various Pelecypoda groups, buried up to 30 cm

deep, representing the endofauna of the mangrove. All these organisms are

marine-affiliated but must also endure temporary aerial conditions during low

tides and the general variations associated with tidal changes (Flores, 1973).

Globally, numerous

studies have been conducted on various aspects of mangrove faunal ecology,

including research on the distribution, zonation, ratio, abundance, density,

and diversity of Mollusca (Pelecypoda and Gastropoda) alongside population

fluctuations over time/season, as well as their associations with substrate

types and vegetation (Emmen & Tejada, 1984). Previous research focused on

mollusks associated with mangroves has primarily emphasized the Pelecypoda

group due to its economic significance and as a food source. Reports indicate

48 species of pelecypods from collections along African coasts, with additional

studies in the west coast of the Americas identifying 11 species, and 10

species noted along the southeast coast of North America, plus 37 species in

the Caribbean and northeast South America (Morton, 1983).

Organisms inhabiting

submerged root regions exhibit impressive adaptation mechanisms, with a

dominance of epizoic, epigenic, and delicate species; some hold significant

commercial value, such as the oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding,

1828) (Lalana & Perez, 1985). This extensive root system supports many

animal groups throughout their life cycles, including fish, shrimp, crabs, and

mollusks (Rützler & Feller, 1988). Consequently, the current study aims to

estimate the occurrence, diversity, and abundance of the Bivalvia class within

the Mollusca phylum, and to elucidate community structure based on the most

significant species within the mangroves of the Chame district. This study will

provide new insights into this taxon for a site with limited biological

information, which may also highlight areas affected by wastewater pollution.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

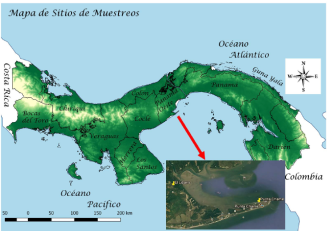

Study Site: Although

Panama boasts 2,800 km of coastline divided into 39% Caribbean and 61% Pacific

regions, high diversity is observed due to habitat heterogeneity with a mix of

biotopes (estuaries, rocky areas, mangroves, sandy beaches, and muddy zones),

partially or fully situated on coastal lands originating from marine areas.

Primarily, the Pacific coast hosts substantial numbers and volumes of benthic

organisms (I.G.N.T.G., 2007).

Main Account: The Chame wetland

comprises mangroves and muddy plains occupying the low area of the Chame River

basin from its mouth to Monte Oscuro Abajo. The Chame mangroves are entirely

flat, attached to a mountain chain like Cerro Campana or Punta Chame, located six

kilometers from the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua (Fig. 1). The most

representative data support the characterization of the floristic and

environmental aspects of a dense mangrove forest extending approximately 59,576

km², covering close to 39,000 km² of muddy plains at the Chame River mouth,

with an average temperature of 27.4°C and annual rainfall varying between 1,200

to 2,000 mm (Flores et al., 2010). Chame is a district in the province

of Panama Oeste, Panama, covering an area of 352.93 km² (136.16 square miles).

The district consists of 11 corregimientos, including El Líbano (Latitude:

8°39'35" N and Longitude: 79°49'45" W) and Punta Chame (Latitude:

8°39'45" N, Longitude: 79°52'51" W) (Panamanglar, 2013), which

represent the quadrants where the research was conducted.

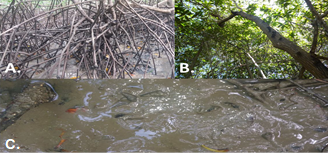

Punta Chame: This part

of the Chame mangrove is situated within the internal area of the mangrove; the

substrate comprises sandy mud. Rhizophora mangle is the dominant species,

followed by Laguncularia racemosa and Pelliciera rhizophorae

(Fig. 2a).

Líbano: This extensive

mangrove area exhibits a high presence of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle),

alongside black mangrove (Avicennia germinans). Water access for this

site is through channels, and the substrate consists of mud (Fig. 2a). Right

along the inner edge of the mangrove, with a sandy-muddy substrate, R. mangle

is the dominant species, with L. racemosa and P. rhizophorae

also present (Fig. 2b).

Figura 1.

Map of the sampling site, El Libano and Punta Chame,

Chame district, West Panama, Panama

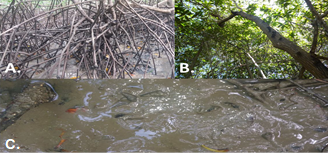

Figura 2a.

A Punta Chame sector, site where the samplings were

carried out; sand-mud substrate. 2b: B Lebanon sector, sampling site with muddy

substrate.

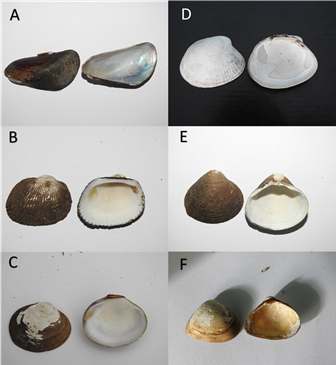

Field Methodology: Two sections were

established in the field: Section A (Punta Chame) and Section B (El Líbano);

each consisting of three quadrants of 100 m², spaced 200 meters apart. Field

outings were conducted during low tide over six months, twice a month. The

dates and times for collection outings were determined using tide prediction

tables for the Pacific of Panama. Three adult mangroves were randomly sampled

within the quadrants, collecting specimens from the mud surrounding the

mangrove, as well as from the roots and trunk. Plastic bags were labeled with

the section, date, and substrate type (trunk, root, or mud) for collecting

biological materials. Only one living representative was taken from each

sample, with all individuals found within the quadrant counted (Fig. 3).

Figura 3.

Substrates where the samples were taken (A. root; B.

trunk; C. mud).

Laboratory Procedure: The collected material

was deposited in the Malacology Museum of the University of Panama (MUMAUP) for

identification. Prior to identification, the soft bodies of the specimens were

separated from the shells and then dried in an oven. Identification was based

on the morphological characteristics of the shell, including the aperture,

siphonal canal, and, for some gastropods, additional information such as folds

or teeth on the inner lip; types of teeth and muscle scars in Pelecypoda.

Taxonomic identification was assigned using "Seashells of Tropical West

America" (Keen, 1971) for Gastropoda and Pelecypoda, and "Bivalve

Seashells of Tropical West America" (Coan & Valentich-Scott, 2012)

exclusively for Pelecypoda. Taxonomic updates were cross validated against the

World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS, 2025).

Statistical Analysis: Data processed during

the research were tabulated using Excel. The statistical analysis utilized in

this study employed the Past 3.0 software along with mathematical calculations

such as the Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H’), Dominance (D’), and Equitability

(J’).

Commercial Mollusk

Survey: To better understand the species utilized in our studied locations, a

survey was conducted with 40 individuals regarding consumption and extraction

of shellfish. Questions addressed frequency of consumption, most consumed species

by residents, product origin, and perceptions of population declines.

RESULTS

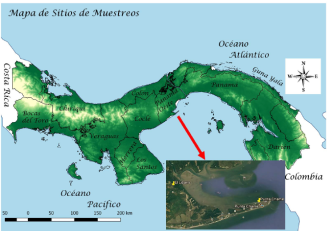

A total of 303

individuals were recorded across six families and seven species in six genera;

the genus with the highest number of species was Polymesoda Rafinesque

1820, represented by two species. The highest counts obtained through genotypic

technology were Leukoma asperrima (G.B. Sowerby I, 1835) (135 organisms;

44.55%), while Isognomon recognitus (Mabille, 1895) was represented by a

single specimen (0.33%) (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Among the substrates, roots (one

individual) and mud (302 individuals) were the only habitats where specimens

were found, totaling 303 individuals. In the roots, only I. recognitus

(0.33% of total) was present in the root substrate (Table 2); L. asperrima

was the most representative species within the mud, comprising 135 individuals

(44.55%) (Table 2). The Pelecypoda class exhibited an H' index of 1.509, while

data based on Dominance (D') revealed a higher value within the class

Pelecypoda (Table 4).

Punta Chame (Sector A):

Two families were accumulated in this site, located at the inner edge of a

mangrove with sandy-muddy substrate (303 individuals from two orders, six

families, six genera, and seven species). The genus with the highest number of

species was Polymesoda represented by two species, with L. asperrima

being the most common, totaling 135 individuals (44.55%). Conversely, I.

recognitus had one specimen and constituted 0.33% of the total species

(Table 1). The pelecypods were confined to the root substrate (one individual)

and the mud (302 individuals), totaling 303 individuals. Within the root

substrate, only one individual of I. recognitus was found (0.33% of

total); L. asperrima was the most representative species in the mud with

135 individuals (44.55%) (Table 2). The Pelecypoda class exhibited a diversity

index of H’=1.509, with a dominance value (D’) of 0.2797 and equity of

J’=0.7754 (Table 4).

Líbano (Sector B): The

fact that this mangrove ecosystem is located at the outer edge refers in this

case to the association of bivalves with the mangrove or the muddy substrate. A

clear vertical capture of samples from trunk, root, and mud showed that only 16

marines Bivalvia (Pelecypoda) were present within four species belonging to

four genera and families. The dominant genus was Anadara Gray, 1847,

with Anadara tuberculosa G.B. Sowerby I, 1833 being the most

representative species (Fig. 5), comprising 11 specimens and constituting 0.23%

(Table 1 and 3). The corresponding diversity index for the Pelecypoda class was

H’=0.9507, with equity J’=0.685 and dominance D’=0.5078 (Table 4).

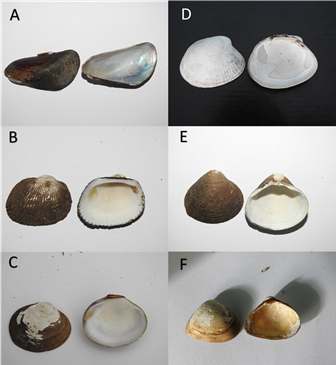

Figura

4.

Chame

Bay Pelecypods: A. Mytella guyanensis. B. Anadara

tuberculosa, C. Polymesoda notabilis, D. Leukoma aspérrima, E. Polymesoda

inflata, F. Panamicorbula ventricosa.

Figura

5.

Anadara

tuberculosa (Sowerby, 1833) la especie más consumida y la más sobreexplotada de

la Bahía de Chame, Chame, Provincia de Panamá Oeste.

DISCUSSION

Seven species of

Pelecypoda, six genera, and six families were observed, totaling 319

individuals. Previous studies in the Pacific of Panama, particularly in

Veraguas, have documented collections conducted by Hertlein in Bahía Honda

(Strong & Hertlein, 1939) using drags and manual collection by local divers

studying coral reefs. In Aguadulce, Tejera and Avilés (1975-1976) identified 35

species of pelecypods; Diéguez and Avilés (1981) recorded 83 species of

commercially important pelecypods in the mangrove area of Bahía de Chame;

Gonzáles (1983) reported 35 pelecypods in the Pacific coast (in the districts

of Zona and Las Palmas); Morao (1983) noted 22 species in the northeastern

coast of Venezuela between January and March of 1983; Avilés (1984) documented

45 pelecypods; Emmen & Tejada (1950) studied the distribution, abundance,

and diversity of Pelecypoda in a mangrove in Aguadulce, finding 12 species of

pelecypods; Lalana & Perez (1985) collected 14 species in the mangroves of

Laguna and 23 species for the mangroves of the Caribbean cays of Cuba; Flores

& Morales (2001) reported 89 species of bivalves from the sands of Santa

Catalina and in their study on the diversity and abundance of pelecypods,

Fairchild & López (2010) identified a total of 52 species of Bivalvia.

Comparisons between

studies in Brazil and other regions indicated that this class is less diverse

and abundant in mangroves, a situation like our findings, supported by Frith et

al. (1976), who discovered that Pelecypoda distribution was rare in

mangroves with salinity fluctuations due to tides, while occurrence within

mangroves was higher under relatively stable saline conditions. While the

number of pelecypods recorded in our study is low, this outcome may be

explained by the proximity of the sampling sites to estuaries with significant

salinity variations. Most organisms exhibit general behaviors that restrict

their activities to favorable habitats (Meadows & Campbell in Spight,

1977), making habitat selection a crucial factor influencing distribution

patterns. The quality and quantity of species are contingent upon tidal range,

wave intensity, and substrate type (Vegas, 1971); species that avoid wave

impacts and desiccation stress by burying themselves in sand or mud are found

in sandy and muddy substrates. Conversely, although sand is more frequently

disturbed, species deposited in these areas are less exposed and less likely to

be moved (Rodríguez, 1967); consequently, we observed a higher number of

individuals in the mud.

Species diversities (H')

in our two study areas were as follows: Punta Chame H’= 1.835 and El Líbano H’=

1.596. Both indices are notably low, confirming that Punta Chame is more

diverse than El Líbano, as indirectly demonstrated by the higher number of individuals

seen in the physical data. This is evident in the dominance values, with D’=

0.2035 for Punta Chame, while El Líbano had a slightly higher value D’= 0.2543,

indicating communities where species are numerically superior to others. Punta

Chame (J' = 0.6777) is comparable to some countries regarding equity value,

while El Líbano (J' = 0.6422) appears low for that group. Both sites exhibited

low diversity; however, Punta Chame (H’=1.835) showed slightly greater

diversity than El Líbano (H’=1.596). Punta Chame is situated at the inner edge

of the mangrove, closer to the beach, whereas El Líbano lies at the outer edge

of these forests, nearer to continental or human-populated areas.

The results of the

dominance and equity indices suggest a homogeneous distribution; both sites

display an equitable distribution of species, although the physical data imply

marked dominance, aligning with Margalef (1995), who indicated that in a

community where one species numerically dominates another, community diversity

is low. The low diversity values are associated with significant sedimentation

in El Líbano and pollution generated by human activities; hence, our records

are considerably lower than those documented by other authors throughout the

Panamanian Pacific, such as in studies conducted in Bahía de Chame (Diéguez

& Avilés, 1981) and in Líbano (Fairchild & López, 2010). Specifically,

Ortega et al. (1986) noted that communities differ in species diversity

in relation to substrate type, dehydration risks, predation, and food

availability. Mollusk diversity, as stated by Jackson (1972), is influenced by

environmental factors such as turbidity, temperature, water pH, salinity, and

grain size.

The mollusk species

collected by us and consumed by the local population include A. tuberculosa,

known as black shell, a significant source of protein and economic resource

among coastal inhabitants, typically consumed in ceviche, rice dishes, among

other recipes (Tejera et al., 2016). We found it to be the most

exploited species in the area and along the Pacific coast; M. guyanensis

is frequently harvested, adhering to roots and forming part of the human diet.

Its soft flesh is nutritionally valuable as a protein source, ranking second

internationally in species consumed after sardines (Tejera et al.,

2016); L. asperrima, the white clam, is edible and used in cocktails,

ceviches, and rice dishes (Tejera et al., 2016); P. ventricosa is

consumed in Bahía de Chame, although many residents are unaware, as they are

sold in mixed "clam" bags (Tejera et al., 2016); species such

as P. inflata and P. notabilis are also consumed in small

quantities. The genus Polymesoda, native to the Americas, is the most

exploited fishery resource in countries like Colombia and Venezuela, and it is

classified as "vulnerable" on the list of threatened species in the

Colombian Caribbean (INVEMAR, 2002). The deforestation of mangroves for

charcoal production, excessive shrimp extraction by external individuals for

sale, pollution, and its impact from shrimp farm development are likely

responsible in varying proportions (Macintosh, 1988 and Macintosh & Ashton,

2002).; also, in this document); all of this has led to reductions in available

stocks for artisanal fishers in this area. The mollusk species most consumed by

residents, in order, are: A. tuberculosa, M. guyanensis, L.

asperrima, P. ventricosa, P. inflata, and P. notabilis;

in this regard, the data gathered from the survey and other studies suggest

that no other species harvested by the inhabitants of Punta Chame Bay (and

likely along the Pacific coast of Panama) has been subjected to greater fishing

pressure than A. tuberculosa (Nagabhushanam & Dhamne, 1977).

CONCLUSION

The observed low

population levels and limited diversity of these species in the mangroves of

the Chame district can be largely attributed to anthropogenic activities such

as mangrove deforestation for charcoal production, excessive extraction by

external settlers for commercial purposes, pollution, and the establishment of

shrimp farms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We

would like to thank with all our hearts our advisors: Janzel Villalaz, Victor

Tejera and Daniel Emmen who thanks to their knowledge have achieved an

excellent work of our thesis, to the staff of the Malacology Museum of the

University of Panama (MUMAUP), for providing us with a space to carry out the

laboratory work, and without leaving behind our colleagues Jean Carlos Abrego,

Freddy Nay, Eddier Rivera, Helio Quintero, Enós Juárez, Isela Guerrero,

Alejandro Ávila, Emeli Barrios, Jessenia Espinosa, who contributed their time

to accompany us on our field trips, also to Mr. Casimiro Calles for lending us

his machete on the sampling days and to Mr. Carlos Abrego for giving us lodging

and food every day that we needed to go to the field.

REFERENCES

Avilés,

M.C. (1984). Moluscos provenientes de la Isla Pedro Gonzáles, Archipiélago de

las Perlas, Panamá. Donax panamensis, 37,21.

Cárdenas-Calle,

M. & Mair, J. (2014). Caracterización de macroinvertebrados bentónicos de

dos ramales estuarinos afectados por la actividad industrial, estero Salado –

Ecuador. Revista

Intrópica,

9, 118-128.

https://revistas.unimagdalena.edu.co/index.php/intropica/article/view/1439/819

Coan,

E.V. & Valentich-Scott, P. (2012). Bivalve seashells of tropical west

America. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Monographs. Santa Barbara,

United State.

Connell,

J. (1961). Effects of completion, predatory by Thais lapillus and other

facture on natural populations of the barnacles Balanus balaniudes. Ecological Monographs, 31, 61-103.

Diéguez,

M. & Avilés, M.C. (1981). Contribución al conocimiento de los bivalvos de

interés económicos del pacifico de Panamá. Panamá: II congreso Nacional de

Acuicultura Memorias MIDA, Panamá.

Emmen,

D. & Tejada, R. (1984). Estudio De la Distribución, Abundancia y diversidad

de Pelecípodos y Gasterópodos de un Manglar del distrito de Aguadulce. Tesis.

Panamá, Panamá.

Fairchild,

N.M & López S.I. (2010). Diversidad y Abundancia de Moluscos de Manglar

(Bivalvos y Gasterópodos) en el Líbano y áreas adyacentes en la Bahía de chame,

Provincia de Panamá. Tesis. Panamá, Panamá.

Flores,

C. (1973). La familia Littorinidae (mollusca: Mesogastropoda) en las aguas

costeras de venezuela. Boletín del Instituto Oceanográfico de la Universidad de

Oriente, ubicado en Cumaná, 12, 3-22.

Flores,

O. & Morales, L. (2001). Moluscos de la clase Pelecypoda y Gastropoda de la

ensenada e isla Santa Catalina, pacifico veragüenses. Tesis. Panamá, Panamá.

Franz,

D. (1976). Benthic assemblages in relation to sediment gradients in the

northeast Long Island sound. Malacología, 15(2), 372-399.

Frith,

D.W., Tantanasiriwong, R. & Bhatia, O. (1976), zonation and abundance of

macrofauna on mangrove shore, Phuket Island. Research Bulletin Phuket Marine Biological Center, 10,

1-31.

Gaxiola,

M. (2011). Una revisión sobre los manglares: características, problemáticas y

su marco jurídico. Importancia de los manglares, el daño de los efectos

antropogénicos y su marco jurídico: caso sistema lagunar de Topolobampo. Ra

Ximhai: revista científica de sociedad, cultura y desarrollo sostenible, 7(3),

355-369.

Gonzalez,

G.R. (1983). Informe de las especies de molusco colectadas durante la gira de

barro colorado salud. No. 7 a la costa Pacífica de Veraguas. Donax

panamensis, 29, 66-72.

Haven,

S. 1971. Niche

differences in the intertidal Limpets Acmea scabra and Acmea

digitales in Central California. Veliger, 13, 231-248.

Instituto

Geográfico Nacional Tommy Guardia (IGNTG). (2007). Atlas Nacional de la

República de Panamá. 4ta edición. Quebecor World Bogotá. Editora Novo Art S.A.

Colombia.

INVEMAR.

(2002). Informe del estado de los ambientes marinos y costeros de Colombia: Año

2002. Serie de Publicaciones Especiales INVEMAR, No. 8, Santa Marta, Colombia.

Jackson,

J. (1972). the ecology of the mollusks of Thalassia communities,

Jamaica. West

Indies. II. Mollusks population variability along an enviromental stress

gradiente. Marine

biology, 14, 304-337.

Jiménez,

J.A. (1994). Los manglares del Pacífico centroamericano. UNA, Costa Rica.

Keen,

A.M. (1971). Seashells of Tropical West America. Marine Mollusk from Baja

California to Perú. Stanford University Press. Stanford, California, United

State.

Lalana,

R. & Pérez, M. (1985). Estudio

cualitativo y cuantitativo de la fauna asociada a las raíces de Rhizophora

mangle en la cayería este de la Isla de la Juventud. Revista de

Investigaciones Marinas, VI (2-3), 45-57.

Macintosh,

D.J. (1988). The ecology and physiology of decapods of mangrove swamps.

Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, 59, 315-341.

Macintosh,

D.J. & Ashton, E.C. (2002). A Review of Mangrove Biodiversity Conservation and

Management. Centre for Tropical Ecosystems Research, Aarhus, Denmark.

http://mit.biology.au.dk/cenTER/index.html

Margalef,

R. (1995). Aplicacions del caos determinsita en ecologia (pp 171-184) En: Flos,

J. (ed.) 1995. Ordre i caos en ecologia. Publicacions Universitat de Barcelona,

España.

Morao,

A. (1983). Diversidad y fauna de moluscos y crustáceos asociados a las raíces

sumergidas del mangle rojo, Rhizophora mangle en la Laguna de la

Restinga. Tesis. Universidad de Oriente, Venezuela.

Morton,

B. (1983). Mangrove bivalves. In The Mollusca: Ecology. Russell-Hunter.

Nagabhushanam,

R. & Dhamne, K.P. (1977). Seasonal gonadal changes in the clam Paphia

laterisulca. Aquaculture, 10, 141-152.

Newell,

G.E. (1958). The behavior of Littorina littorea (L). under natural

conditions and its relations to position on the shore. Journal of the Marine

Biological Association UK, 37, 229- 239.

Olguín,

E., Hernández, M. & Sánchez, G. (2007). Contaminación de manglares por hidrocarburos y estrategias

de biorremediación, fitorremediación y restauración. Revista internacional de

contaminación ambiental, 23(3), 139-154. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-49992007000300004&lng=es&tlng=es.

Ortega,

S. (1986). Fish predation on the gastropods in the Pacific coasts of Costa

Rica. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 97, 181-191.

PANAMANGLAR.

(2013). http://panamanglar.org/es/listing/bahia-de-chame/

Pfaff,

M.C. & Nel, R. (2019). Intertidal zonation. Reference module in earth

system and environmental sciences. Second Edition, United States. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11184-4

Pomareda,

E., & Zanella, I. (2006). Diversidad

de moluscos asociados a manglares en isla San Lucas. Revista de Ciencias

Ambientales, 32(1), 11-13.

Rodríguez,

G. (1967). Comunidades bentónicas. En: Ecología marina. Eds: fundación La Salle

de Ciencias Naturales. Argentina.

Rützler,

K. & Feller, C. (1988). Mangrove swamp communities. Oceanus, 30, 16-24.

Spigth,

T.M. (1977). Diversity of shallow water Gastropod Communities on temperature

and tropical beaches. The American Naturalis, 3(982), 1077-1097.

Strong,

A.M. & Hertlein, L.G. (1939). Marine mollusk from Panamá collects by Allan

Hancock Expedition to the Galapagos Islands, 1931- 1932 En: Allan Hancock

pacific vol. 2 (12), p.177-184. California: The University of southern

California press, United States.

Tejera,

V.H. & Avilés, M.C. (1975). Lista de gasterópodos de la costa del Distrito

de Aguadulce, Provincia de Coclé, República de Panamá. Conciencia, 2(2), 5-6 y 15.

Tejera,

V.H. & Avilés, M.C. (1976). Inventario de flora y fauna de costas del

distrito de Aguadulce. Primera parte: Clase Pelecypoda. Conciencia, 3(3),

10-11.

Tejera,

V.H., Avilés, M.C. & Córdoba D. (2016). Moluscos Intermareales del Distrito

de Aguadulce. Guía de campo. Imprenta: Color Group Internacional. Panamá,

Panamá.

Vegas,

M. (1971). Introducción a la ecología de los bentos marinos. O.E.A Washintong D.C.;

United States.

WORLD

REGISTER OF MARINE SPECIES (WoRMS). Editorial Board (2025). World Register of

Marine Species. Available from http://www.marinespecies.org

![]() , Joan Antaneda2

, Joan Antaneda2 ![]() Guadalupe

Ureña3

Guadalupe

Ureña3

![]()